Rationing

To aid the war effort, rationing of essential commodities such as food, clothing, rubber and petrol was instituted in all Allied countries early in World War II. It became patriotic to ‘go without’ luxuries in support of troops overseas and industrial production of equipment and supplies for the forces.

Rationing in Australia during World War II

In Australia rationing regulations for food and clothing were strictly introduced in mid-1942 to manage shortages and control civilian consumption. It also aimed to curb inflation by reducing consumer spending, hopefully leading to a higher level of savings by the population and greater investment in the government war loans program.

Rationing in Australia was less harsh than in the United Kingdom where a blockade of the north Atlantic by German U-Boats resulted in huge shortages of food materials, causing heavy rationing regulations to be imposed on the British population. At no time were the same drastic conditions imposed on Australia which was fortunate in possessing a large and well developed rural production industry. Nevertheless the use of food ration coupons was applied to clothing, tea, sugar, butter and meat. From time to time eggs and milk were also rationed during periods of shortage.

Rationing was administered by the Rationing Commission. The process of food rationing was based on the purchase and surrender of coupons before rationed goods could be supplied. The person responsible for enforcing rationing was John Dedman, Minister for War Organisation of Industry. He was also the Minister in charge of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. From 1942 as the range of rationed commodities grew, critics of Dedman’s measures referred to him as ‘Lumbago Jack’. He even banned retail advertising during Christmas 1942, to curb unnecessary spending.

Rationing of food and clothing

Not every Australian embraced the war effort, with some prepared to exploit and profit by selling scarce commodities at greatly inflated prices. The demand for controlled commodities created a ‘black market’ where commodities could be acquired without coupons but at high prices. Even coupons became a commodity with a negotiated price. However, rationing was policed and breaches were severely punished. Breaches of rationing regulations were punishable under the provisions of National Security Regulations. Fines of £100 or up to six months imprisonment were imposed. Responding to complaints that these penalties were inadequate, the government passed the Black Marketing Act at the end of 1942. This legislation was for more serious cases and could carry a minimum penalty of £1000.

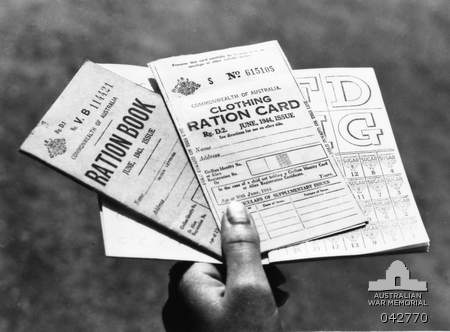

Australia followed British procedures for the introduction of rationing. Shops were made ready for the change from a cash to a coupon economy. Each adult Australian citizen received a ration book with 112 coupons. All purchasable items had a coupon value, for example a man’s suit cost 38 coupons whereas a pair of socks cost only four coupons. Used coupon books were exchanged for new ones annually and people had to plan their expenses to avoid spending all their coupons within twelve months.

Regulation of rationed goods was based upon quantity and supply. The following table outlines how goods were initially allocated and the dates that the restrictions were imposed and removed:

| Item | Date gazetted | Date abolished | Quantity per adult |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clothing | 12 June 1942 | 24 June 1948 | 112 coupons per year |

| Tea | 6 July 1942 | July 1950 | 1 lb per 5 weeks |

| Sugar | 29 August 1942 | 3 July 1947 | 2 lb per fortnight |

| Butter | 7 June 1943 | June 1950 | 1 lb per fortnight |

| Meat | 14 January 1944 | 24 June 1948 | 2 lbs per week |

In Queensland, the impact was lessened by larger suburban blocks allowing many families to grow their own vegetables and fruit. In some cases people had blocks big enough to support their own cow and supply themselves with butter, cream and milk. The government feared that rationing would result in deterioration in health on the home front but, in fact, the outcome was positive. Rationing resulted in a decline in diet related problems like obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

Fish, sausages, chicken, ham and rabbits were not rationed. Recipes designed to cater for the lack of eggs, butter and meat appeared in newspapers and magazines on a regular basis. Animal parts such as brains, tripe, livers and kidneys were more readily available than better cuts of meat during the war and formed a significant part of people's diets. Shopping for essential goods and rationed commodities often meant standing in long queues.

The Austerity Campaign

war effort, supplies of non-military goods dwindled. There were shortages of civilian clothing. People were encouraged to reuse clothes. Cheaply-made ‘austerity’ garments replaced clothing stocks as they were sold out. Made from materials non-essential to the war effort, ‘austerity suits’ appeared for men and became a badge of pride in support for Australian troops fighting abroad.

The ‘Austerity Campaign’ meant going without luxury items and involved living as simply as possible. The campaign was launched alongside the Austerity Loan program. The message was ‘Save’ and ‘Save Australia’. People were told to:

- Smoke less—burn less money.

- Drink less—satisfy a need not a habit.

- Plan meals for their food value.

- Give up cosmetics—it’s smart to be natural.

Children’s toys were often hand-made and the Country Women’s Association of Queensland mounted an exhibition in Brisbane in 1943 to display the types of toys that could be cheaply produced.

The character of the ‘Squander Bug’ became a focal point for the campaign to restrict unnecessary spending in society. The bug was characterised by reference to the Japanese ‘Rising Sun’ emblem, on the fat belly and demonised by devil-like ears and a forked tail.

Petrol Rationing

At the start of World War II Australia was totally unprepared for an extended conflict and had sufficient petrol reserves for only three months of normal consumption, and limited storage capacity. The Commonwealth War Book simply noted that on the threat of war the Department of Supply should prepare a plan for the rationing of petrol. However, fuel rationing was not immediately imposed, with the government preferring instead to appeal to the community to be frugal with petrol.

As an alternative, the government encouraged motorists to use charcoal gas producers, which were fitted to the back of vehicles. However, gas producers were not popular with the public. They were in short supply, cumbersome and not particularly efficient. As well, refuelling with charcoal was a messy process. No amount of attractive propaganda could overcome these shortcomings.

The motor industry lobbied against any form of petrol rationing, claiming that it would lead to personnel dismissals and economic instability in the industry. Although the Federal government believed that rationing should only be introduced as a last resort, the Director of Economic Planning, Ernest Fisk, subsequently announced that he would introduce a scheme to conserve petrol, which would ‘make a man ashamed to use his car unnecessarily’. All users were to be divided into classes, such as private cars, delivery vehicles, buses, taxis, trucks, industrial transport and farm machinery, and priorities determined for each classification. Ration scales took into account the horsepower of vehicles so that miles-per-gallon could be calculated before allowances were allocated. Finally, the various groups were divided into essential, preferred or ordinary user status. The task was enormous.

The scheme finally devised for petrol rationing was very complicated, and produced a large amount of paperwork. Over a million Australian civilians applied for petrol licences. To obtain ration tickets applicants had to complete and present an ‘Application for Ration Tickets’ every time tickets were required. Petrol rationing was introduced in Australia in late 1940 and early 1941, but was not strictly enforced until 1942.

The first ration tickets had a currency of six months. After that, issues were made every two months, to avoid forgeries and black market hoarding. Attempting better management of petrol supplies, the government proposed the pooling of petrol supplies under its control as this enabled more efficient use of the storages owned by the various oil companies. Under pooling, the use of company brand names was abolished. Storage facilities grew up all over Queensland and supplied civilian and military vehicles alike.

Victory over Japan in 1945 raised expectations that rationing would be abolished quickly, but rationing was only gradually phased out as Australia continued to support Britain with food parcels and exports for a number of years. In the United Kingdom, the meat ration had been further reduced and in an effort to support the British public, the Australian Government maintained meat rationing and price controls until 1948.

June 1944. Ration books for food and clothing (AWM 042770)

June 1944. Ration books for food and clothing (AWM 042770)